FIRST AMERICANS – ART AND ARTIFACTS TELL THEIR STORY

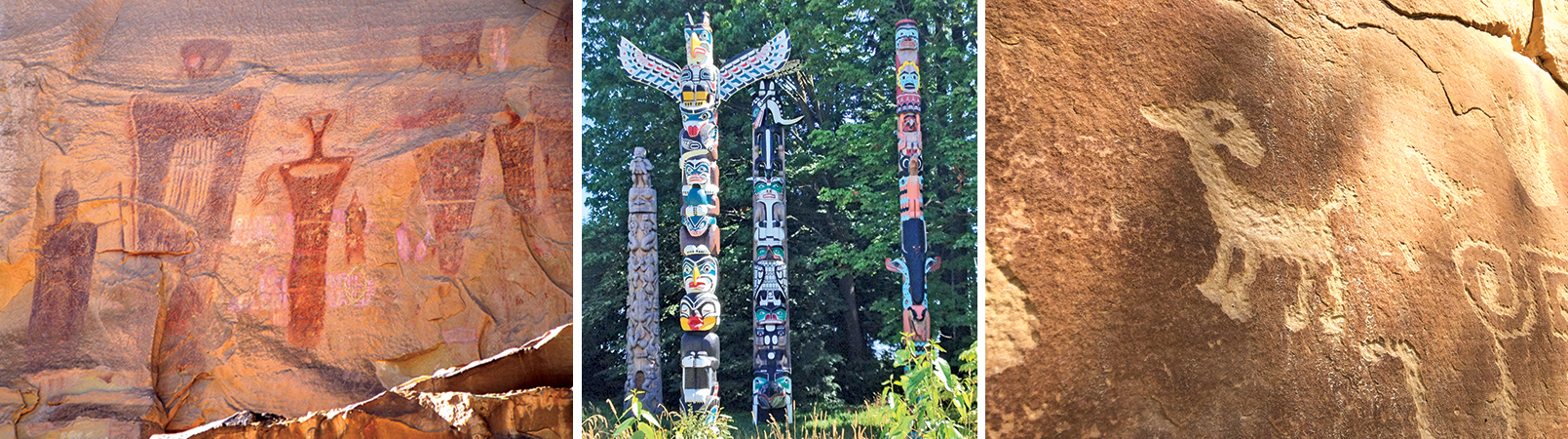

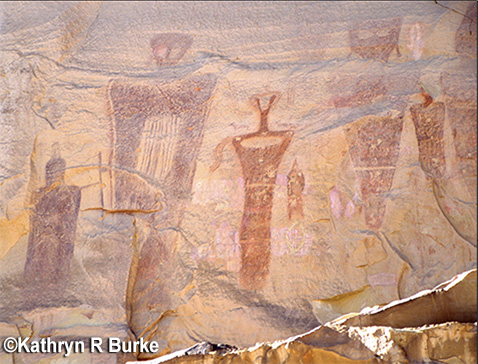

Sego Canyon, Utah, petroglyph, © Kathryn R. Burke; Tiglet totems Stanley Park, Vancouver, Washington, © Kathryn R. Burke; Mesa Verde petroglyph, © Laurie Casselberry.

Eight major groups of indigenous peoples occupied the North American continent before the first European explorers and settlers arrived. Six of them occupied the vast expanse west of the Mississippi: Pacific Northwest Coast, California, Plateau, Great Basin, Southwest, and Great Plains. To the east, where the European settlers first landed, were the Northeast Woodlands and the Southeast, which had the largest population when European explorers, beginning with the Vikings, over 500 years before Columbus, first set foot on North America.

[San Juan Silver Stage | November 2021 | Kathryn R. Burke]

Since we don’t have a time machine — yet—we can’t physically go back in time and see history in the making. But, we can still observe it, because those who made history left behind a wealth of artifacts for us to examine. Whether we find these items in situ, or visit them in museums and private collections, we can follow their owners’ past history in the present time.

Scientific study and historical research suggest that the indigenous peoples were here long before the white man appeared, arriving more than 20,000-30,000 years ago! They migrated over a glacial land bridge, known today as Beringia, which connected Asia to the Americas, likely following the large game which was a primary food source. “The First Americans were extraordinarily adept at moving over the landscape,” said David Meltzer, an archaeologist at Southern Methodist University. “Their entire existence—was about adapting. They had a toolbox of tactics and strategies.”

Practical Art. They left behind plenty of evidence of both, through art and artifacts that share their stories. Tools tell how they survived—feeding, clothing and sheltering themselves. Baskets, pottery, and various decorative items show how they combined artistry with practicality.

L-R: Apache baskets; Zuni lizard pot; Navajo horsehair pot; Beaded bear claw medallion, Wanda Jacket. Photographed at Ute Indian Museum. © Kathryn R. Burke

Rock art, in the form of petroglyphs (“pecked” or chiseled into rock) and pictographs (paintings or drawings on rock surfaces), give us a visual of their way of life, a sort of “map” of their evolving existence. Native Americans frequently refer to the figures as “Indian writings” and were able to read and write them on rocks for thousands of years. Some also shared their history with colorful “totem” poles, wood carvings, basketry, pottery, and beadwork. The type of art they created was influenced by location and lifestyle—nomadic tribes preferred easy transportable artifacts, for example.

Pictograph. Sego Canyon, Utah. Sego Canyon contains three culturally distinct styles of rock art: Fremont, Ute and Barrier-style. The Canyon is just west of the Colorado border.

“The peopling of the new world” (from the Arctic to the Amazon) “remains one of humanity’s greatest achievements, a feat of endurance and adaptation not to be equaled,” wrote 20th-century French archaeologist François Bordes.

“Armed with an expert knowledge of nature… the earliest Americans and their descendants were resourceful trailblazers who peopled the longest geographical expanse ever settled by humans. Braving the unknown, they adapted masterfully to a vast array of ecosystems on two continents,” wrote archaeologist David Anderson of the University of Tennessee, “and soon diversified into many hundreds of culturally distinct nations and tribes. By the time European explorers arrived, it is estimated that more than 50 million people were already living in the Americas! These early Americans deserve our admiration.”

Display of beaded buckskin shirt (worn by Chief Ouray) and bear claw belt purse. Ute Indian Museum exhibit. © Kathryn R. Burke.

European Invasion. The arrival of European explorers who sought to colonize their land through the 16th and 17th centuries decimated large parts of the Native populations through epidemic disease and greed (e.g. the concept of “Manifest Destiny” triggering the deadly “Indian Wars”). [Related story]

Yet, the descendants of many of those early groups are still here. Today, more than 570 federally recognized tribes of American Indians and Alaska Natives live within the continental United States (230 of them in Alaska). The First Americans were, and are, ethnic survivors. Anderson concluded: “I think they exemplify the spirit of survival and adventure that represents the very best of humanity.”

Great Basin Nations. The high desert regions between the Sierra Nevada and the Rocky Mountains were the home of the Utes and Paiutes, and other members of the “Desert Culture” as these groups were sometimes called. The territory today encompasses Western Colorado, Nevada, Utah, Northern Arizona, Southern Oregon and Idaho, parts of Southwestern Montana and Western Wyoming, and Eastern California.

“Our legends say we came from the Bear, and we don’t eat bear meat, and we respect the Bear. We have our Bear dances because of this in the spring—because the Bear is one of the powers that the Great Spirit has given us.” —Alden Naranjo, Southern Ute Indian Tribe. 1988.

Perhaps more than any other group, Great Basin peoples were known for their use of color in pottery, basketry and intricate beadwork, which like their neighbors to the west, incorporated both geometric and figurative design. Baskets were used as a seasonal tool (for harvesting) but were a means of artistic expression that often resulted in very complex designs and elaborate weaves.

One of the best collections of Ute artistry and artifacts resides in the Ute Museum, in Montrose, Colorado. The Utes were Colorado’s longest continuous residents. (Learn more here: historycolorado.org/ute-indian-museum.)

Southwest Peoples occupied present-day Arizona and New Mexico, and parts of Utah, Colorado, Texas and Mexico. Depending on terrain, they divided into two distinct groups: those who lived above the ground and those who roamed over it. The former, known as Ancestral Pueblo or Anasazi, lived in large villages of multi-story dwellings, or pueblos, often built in cave-like crevices in the cliffs, hence earning the name of “cliff dwellers.” Some structures had as many as 1,000 rooms, accessible by wooden ladders that could be pulled out of harm’s way, when villages were under attack. Religious practices also utilized ceremonial pit houses, or kivas. The Pueblo culture is known for weaving and basketry. As agricultural production increased, augmented by irrigation, pottery became important as both as a tool (vessel) and decorative art form.

The name “Anasazi” is a Navajo term, meaning “ancestors of the enemy,” for the Pueblos were mutually hostile with the nomadic tribes such as the ancestral Apache and Navajo. Prolonged drought and continuous conflict between the two groups caused the Pueblo to move south and east, but they never regained the sophistication achieved in earlier eras. The Navajo, influenced by Spanish miners (and horsemen) in the 1700s. and their descendants became known for jewelry-making, especially in silver.

Great Plains Indians roamed a large area from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, and from present day central Canada through Texas. The area was covered with lush grasses that sustained vast herds of buffalo, source of most everything they needed for food, shelter, clothing, weapons, and tools. Following the bison, the people lived in easily transportable tipis (made of dried buffalo hides), and until the re-introduction of the horse—which had been hunted to extinction in pre-historic times—dogs were used for transport. Entire communities participated in driving herds of game over the cliffs. Not all Plains people were nomadic. Some farmed, living in villages along the rivers, which reached populations of 1,000 or more. Their lives were seasonal, sheltering in winter, planting in spring, farming (women) and hunting (men) in summer, and harvesting in the fall.

Display of hunting tools, Ute hunters used bows and arrows to hunt deer. They pursued them by stalking, ambushing, or driving them into hidden holes. Ute Indian Museum exhibit. © Kathryn R. Burke.

The people excelled at embroidery, basket-making, and beading, which was especially prevalent, because it was easily transportable. They decorated their clothing and tipis as well as many of their everyday tools. War clothing was elaborate. Porcupine quills were often woven into the clothing and it was often decorated with beadwork and fringe as a status symbol. Women wore jewelry crafted of seashells, semi-precious metals, and elk tusks.

The Plains Nations, including Sioux, Pawnee, Crow, Cheyenne, Blackfoot, Osage, and Comanche, were the last indigenous peoples to succumb to European colonization, and have often been regarded as the archetypical American Indians. Their culture and lifestyle were popularized by “Wild West Shows,” such as “Buffalo Bill Cody,” and pulp fiction.

East of the Mississippi

The Northeast. The Native Americans of the Woodlands lived in forested areas with lakes, rivers and running water. They hunted, fished and farmed. Most groups lived in villages with permanent homes built of trees and bark: Wigwams (for one or two families) or a Long House (which held up to 30 extended families and could be 300 feet long). Walls or palisades surrounded the villages.. Although the Woodland nations each had their own customs, they all depended on the forests and its resources to survive. For many years the Native Americans of the northeast were at war with each other. When European traders began to buy the furs these people hunted and trapped, the nations, helped by weapons provided by the Dutch and the French, warred with one another to expand their territories’ supply of furs. The main cultures of the Northeast were the Iroquois, Algonquin, Wampanog, and the Cree.

The Southeast. Native populations in this area were the highest of all the regions of North America. The oldest pottery unearthed in North America, dating back to 4,500 years ago, was found on Stallings Island in the Savannah River near Augusta, Georgia. Many of the natives of the Southeast hunted buffalo, deer, and other animals, although the majority of the Native Americans of the Southeast were farmers. The region was home to the Cherokee, Creek Choctaw, Seminole, and Natchez.

Native American Indian Art is as diverse as the peoples who created it. Evolving from simple cave drawings and carvings, traditional American Indian art grew to include intricate pieces (or examples) in such forms as jewelry, beadwork, weaving, pottery, basketry, paintings, dolls, carvings, masks, quillwork (embroidery), and totem poles. Throughout their history their art has reflected their culture, lifestyle, and environment.

The people depended on things like pottery, basketry, wood, and stone to meet basic needs, but they were a highly creative, innovative people. Artistry was an important aspect of their lives; they decorated many of their functional items. They also used artistry to tell their stories, much of which survives today as artifacts. Not only did location and lifestyle determine much of their decorative endeavors, spiritual beliefs also played an important role. This is especially notable in the masks and dolls created by Pueblo tribes such as Hopi and Zuni. Jewelry and personal adornment served many purposes as well. Some, like the Navajo, have become known in modern times for their work in silver, gold, and semi-precious stones, especially turquoise.

Every November, we celebrate and honor their incredible resilience with Native American History Month. To learn more about America’s indigenous peoples, how they lived and resisted foreign invasion, a wealth of historic and scientific information is available in libraries, book stores and online. Less often told, but fascinating to relate, is how art and artifacts record their colorful, resourceful history.

For more information on Indian Arts & Crafts, visit https://native-american-indian-facts.com/Native-American-Indian-Art-Fact

Click here to add your own text